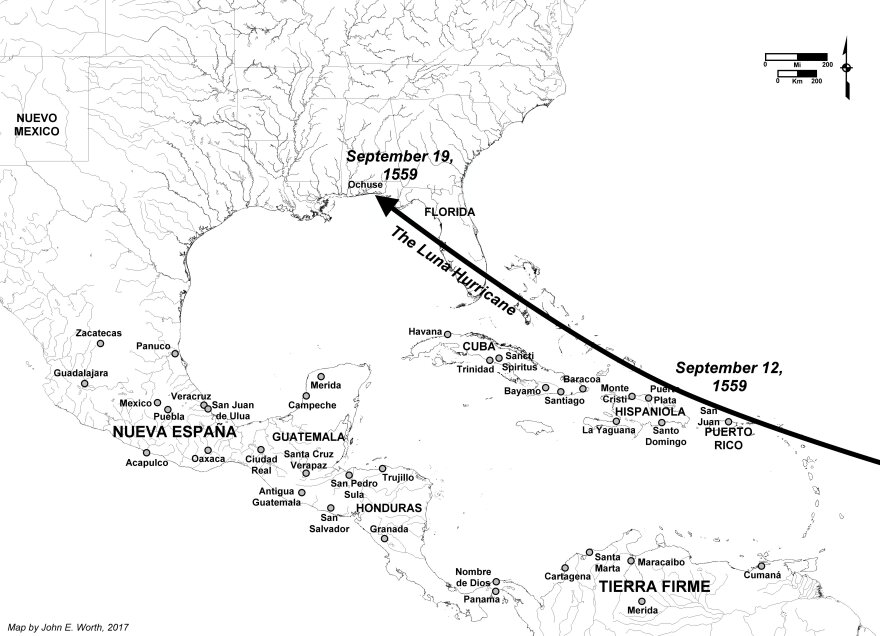

During the evening of Tuesday, September 19, 1559, some 458 years ago, strong winds from the north heralded the arrival of a great hurricane in Pensacola Bay. The storm was not the first to assail the bay, nor would it be the last, but the 1559 hurricane did manage to change the course of human history by destroying a fleet of Spanish colonial ships riding at anchor off the newly-founded settlement called Santa María de Ochuse.

Five weeks earlier, on August 14-15, the fleet of 12 ships carrying some 1,500 soldiers and settlers entered Pensacola Bay (then known by its native name of Ochuse) with the intention of establishing a port settlement, pushing inland to the native chiefdom of Coosa located in modern northwest Georgia, and then crossing the Appalachian summit and descending eastward to found a Spanish colony along the Atlantic coast at a place known as the Punta de Santa Elena, at modern-day Parris Island, South Carolina. Following nearly half a century of failed private attempts to establish a Spanish colonial presence in southeastern North America, King Phillip II had finally provided substantial royal funding and support to launch the largest colonial effort yet attempted in the land they called Florida, in order to block the imminent threat of French colonization.

At the head of the expedition was governor and general don Tristán de Luna y Arellano, veteran of the Coronado expedition to the American Southwest nearly 20 years before. Leading a group of some 550 cavalry and infantry soldiers and nearly 1,000 others including wives and children, servants, slaves, and even a group of some 200 Aztec warriors and craftsmen from the Valley of Mexico, Luna directed his forces to reconnoiter the bay in search of a suitable site for settlement. Discovering a high, level terrace next to a bluff overlooking the heart of the bay, as far inland as possible while still in view of the bay’s mouth, the Spaniards spent the next weeks clearing the forest, laying out a rectangular grid of streets and some 140 land lots, and initiating the construction of housing for the colonists on the landform now known as Emanuel Point. Though many initially refreshed themselves on land after the nearly two-month voyage from Veracruz, documentary records reveal that the settlers promptly offloaded the majority of their equipment, supplies, and personal possessions, leaving only the vast stores of corn, wheat, wine, olive oil, and other staple foods on board the ships until a sufficient warehouse had been constructed to house them on land.

One by one, during early September the ships’ crews were certified to be issued their remaining expedition pay as they completed the offloading process. As the unloading was completed, Luna dispatched a detachment of two companies inland along the Escambia River at the head of the bay in search of native villages and informants who could help guide them to Coosa. While awaiting their return, two ships were even prepped for a transatlantic voyage to make a direct report in Spain, while another was sent back to New Spain to report on the successful landing. All seemed well, and as housing approached completion at the new settlement, attention doubtless turned to public structures such as the royal warehouse.

Even though Spanish residents of Puerto Rico had already been devastated by the approaching hurricane on September 12, Luna’s colonists had no warning when the storm rolled into Pensacola Bay seven days later. Descriptions of the storm indicate that the winds started out of the north, but swirled in all directions around the colony for a full 24 hours, devastating the fleet and young settlement at Emanuel Point. Anchor cables were broken, ships were driven into shallower water and literally broken apart by the waves and wind. On board the flagship Jesús, ready to sail for Spain, its captain Diego López drowned, as did one of the Dominican missionaries named fray Bartolomé Matheos, and a soldier named Melchor González. While the total loss of life on the ships is unknown, nearly all the food stores for the colony were destroyed with the ships. Only a single small vessel was reported to have “miraculously” ended up on dry land in the midst of a grove of trees, and which was completely scavenged afterward. Documents suggest the settlers fared better on land, but the fledgling settlement was doubtless devastated after only a few weeks of clearing and construction. And most importantly of all, Luna was now in charge of well over a thousand people who had virtually no food available to them, and only four ships still afloat, including a caravel, two barks, and a small frigate. One of the barks was sent to Veracruz with the tragic news, and another to Havana for emergency supplies. Two hundred soldiers were also quickly dispatched deep inland to the north in search of native populations with food supplies.

For the Luna colonists, the struggle to survive had just begun. The next two years would witness an amazing and dramatic sequence of events, including the relocation of most settlers into central Alabama at a native town called Nanipacana for some four months, the arrival of four successive relief fleets from New Spain, the gradual evacuation of more and more of the settlers from Florida, and a series of bitter legal disputes between Luna and his followers, which generated much of the documentation that remains of the expedition. But that is another tale. On another Tuesday, September 19, Pensacola was the scene of a massive hurricane that changed the history of North America forever, illustrating the pivotal role that such storms played and continue to play in human affairs.